It’s a wonderful breakthrough when a student says, “Wow, that was actually easier than I thought!”

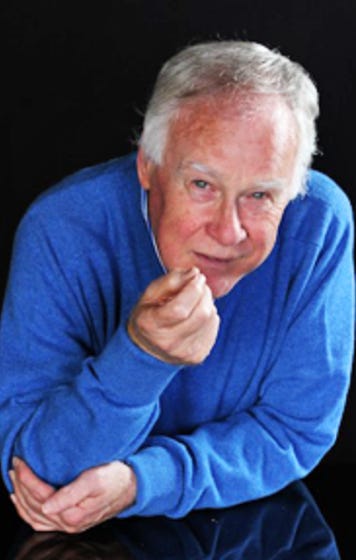

Geoffrey Madge

Foreword

PianoVrienden is deeply honored that Geoffrey Madge took the time for an interview. As a pianist, teacher, and masterclass instructor, he ranks among the greatest in the piano world. His entire life is devoted to the piano; he quite literally breathes music. His repertoire is immense, his technical knowledge unparalleled, and his home reflects his profound love for everything related to piano playing. Geoffrey Madge possesses an exceptional musical and empathetic ability, allowing him to truly understand and guide each student in a personal and fitting way. His passion for passing on his vast knowledge and experience to the next generation is truly admirable. PianoVrienden had the privilege of standing beside his two magnificent Steinway grand pianos, not only to hear Geoffrey’s insights but also to experience his inspiring passion. We are deeply grateful for this opportunity.

Biography & Education

You started playing the piano at the age of eight. What do you remember from those early lessons, and what drew you to the instrument?

My first interest in the piano began when I heard my mother playing Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies. I remember my piano teacher saying that I shouldn’t finish the music books she gave me so quickly because it was getting expensive for my parents. I would work through each new book within days!

How did your encounter with Benno Moiseiwitsch influence your musical path?

When I was 12 years old, my mother took me to a piano recital by Benno Moiseiwitsch. It changed my whole life. I still remember every note, the sound, and the way he played.

What motivated you to move to Europe in 1963, and why did you choose to settle in the Netherlands?

I had won all the major competitions in Australia, including a Bach championship and the most important Australian competition in Sydney, where I won with a performance of Brahms’ Second Concerto at the age of 19.

Following this, the director of the conservatory (Prof. John Bishop) and my teacher (Clemens Leske, a student of Edwin Fischer) encouraged me to move to Europe to further my studies.

What impact did your studies with Eduardo del Pueyo and Géza Anda have on your musical development?

I left Australia for Switzerland and auditioned for Géza Anda. I didn’t realize there were about 60 other pianists auditioning as well! Fortunately, I was chosen along with three others. I worked extensively on Brahms’ Second Concerto with him.

Later, I studied for about two years with Eduardo del Pueyo in Brussels. Géza Anda had a greater influence on my playing overall, especially in interpretation and developing a singing tone, while del Pueyo taught me about producing a beautiful sound in a very economical way.

Repertoire & Artistic Vision

You are known for performing demanding works such as Sorabji’s Opus Clavicembalisticum. What attracts you to such complex compositions?

While in Australia, I had lessons with an elderly student of Busoni, who assigned me Busoni’s Toccata — one of his most difficult works. This sparked my interest in "unplayable" repertoire.

When reading about music, I encountered the name Sorabji — known for writing unplayable works and forbidding performances. Intrigued, I ordered his works from London, including the mammoth score of Opus Clavicembalisticum. I began practicing it, and although my colleagues thought I was crazy, I ended up performing a large part for my final exam at the conservatorium.

What was your experience performing Opus Clavicembalisticum, and how did you prepare for such a monumental work?

It’s hard to explain in a few words. I was invited to give a recital at the Holland Festival, but first needed Sorabji’s permission, which he had refused to many famous pianists.

By coincidence, I was invited to visit him — he had heard a BBC recording of mine and was impressed — and he gave me permission to perform any part or the complete work.

During my first visit, I played a significant portion for him; he commented, "I didn’t know it was such a good piece."

Preparing for the performance involved developing special strategies, tackling each incredibly difficult section one by one, and often creating alternative fingerings. Two grand pianos were prepared on stage, with microphones for a live broadcast — and even a table with water and a towel in case of collapse! Fortunately, a large audience made the evening a great success.

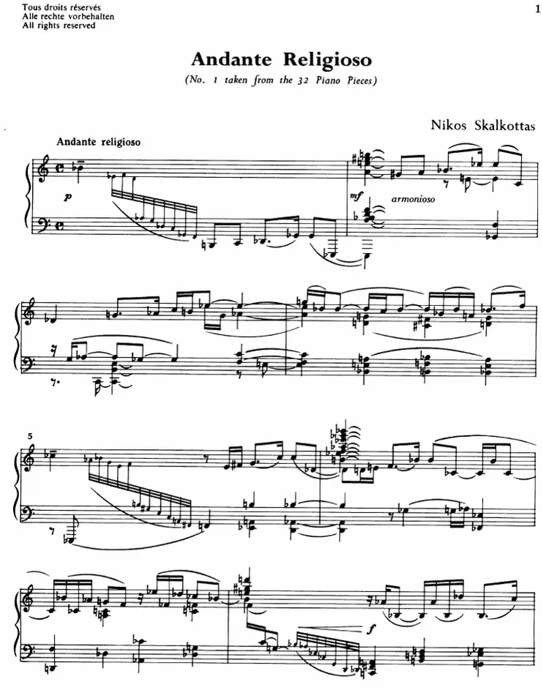

You gave the first complete performance of Skalkottas' 32 Piano Pieces. What fascinated you about his music?

While performing Xenakis' works at a festival in Athens, I gained a reputation for being able to perform highly complex music.

Inspired by this, the top music agent in Greece asked if I would look at Skalkottas' 32 pieces. No one had yet succeeded in performing them all. I decided it was possible, which led to the invitation to perform them complete. Skalkottas, a national hero in Greece, became an important figure in my recording career too, with three of his piano concertos recorded for BIS.

How do you approach interpreting works by composers like Xenakis, Godowsky, and Busoni?

They each require completely different approaches.

Xenakis demands lightning-fast, horizontal movements across the keyboard without looking — and an ability to assign different dynamics to each note, almost like an electrical technique.

Godowsky requires a weighted, gravity-based playing style — very natural and effortless.

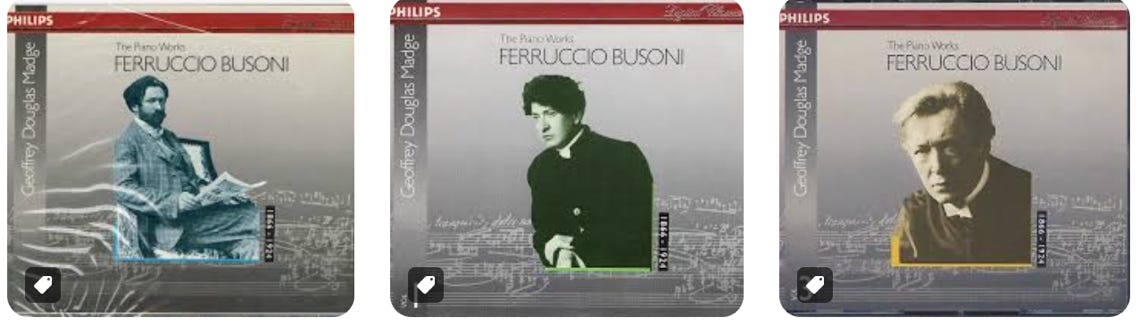

Busoni represents a visionary style, a modern school of piano playing. My fascination with him led to my 6-CD recording project for Philips.

You made an impressive recording of Busoni’s piano works. What appeals to you in his music?

Even his early works, like the 24 Preludes written at age 10, reveal astonishing technical ability.

What inspires me most is his visionary imagination.

Sorabji knew Busoni personally and played for him, which deepened my understanding of Busoni’s playing style. Over the years, I have written several essays on the subject.

How do you balance performing well-known classical works with promoting lesser-known or contemporary compositions?

Performing complex works gives deeper insight into classical compositions. It raises questions: How do we present the entire spectrum of musical literature to modern audiences? This question became a driving force in my masterclasses and recitals series, The Art of Listening.

Pedagogy & Education

As a former professor at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague, what do you see as the most important elements in training young pianists?

If the teacher is inspired, he or she will naturally inspire the student.

Next in importance is ensuring that the technical foundation is strong. A fantastic technique is essential, especially for the level of playing required on today’s concert stages.

Once this is developed, it’s important to reveal to the student the beautiful moments within the great repertoire — encouraging a broad exploration from the pre-baroque era to contemporary works. Curiosity is essential: studying legendary performers, how they played, and why.

What philosophy do you follow in your masterclasses, and how do you try to inspire students?

First, I try to create an atmosphere where the student feels completely at ease — the right environment is crucial for the best results.

I aim to build a dialogue, listening to entire pieces and identifying what already comes across well, based on the score and the student’s own character.

We then work together on any difficulties, celebrating the inspiring moments in the music.

It’s a wonderful breakthrough when a student says, “Wow, that was actually easier than I thought!”

I always try to cultivate interest in the interpretations of legendary musicians — there is still so much to learn from them.

How important do you think it is for young pianists to immerse themselves in both traditional and modern repertoire?

It’s extremely important — but not just classical and modern repertoire. They must explore everything from the late 1600s until today.

Can you share a memorable moment from your teaching career that particularly touched you?

There have been many wonderful pianists who participated in my masterclasses and lessons.

Some performances remain vivid in my memory.

Several of these pianists have gone on to win prizes at international competitions.

Website Geoffrey Madge

Musical Philosophy & Interpretation

You once said that “Bach is in the DNA of every pianist.” Can you elaborate on that?

Bach has influenced everything in the Western musical world — it’s a miracle that this remains true even today.

You could say that Bach is in the DNA of every musician.

His work remains the best study for pianists: mastery of counterpoint, of expression, and of imagination — it’s still so modern.

How do you approach interpreting works by composers like Bach and Beethoven compared to contemporary composers?

They require a different physical approach to the keyboard — partly due to the difference in instruments.

The clavichord, harpsichord, and early fortepiano all demand different touch and tempo considerations.

For example, playing too fast on a clavichord or harpsichord will not sound natural.

When playing Mozart, it’s important to imagine how it would sound on a fortepiano from his time, rather than speeding through pieces mindlessly on a modern grand.

Ultimately, finding the inner logic behind the music helps the listener follow the story, regardless of the period.

What is your view on the role of the pianist as an interpreter versus a composer?

Having worked closely with many composers and having composed myself, I believe composers often perform works differently than pianists who do not compose.

Composers understand firsthand which elements in a piece are most vital — sometimes in ways that performers might overlook.

How does your experience as a composer influence your interpretation of existing works?

It has influenced me greatly.

As a composer-pianist, I tend to look for special events in the music that signal a need for space or emphasis.

I believe we must allow phrases to "breathe."

So much modern performance feels rushed, breathless — just like life today.

In large halls, the further you sit from the piano, the faster the music can seem — another reason to take time and let music unfold naturally.

Composition & Creativity

You have composed several works, including the ballet Monkeys in a Cage. What inspired you to write this piece?

I collaborated with Australian choreographer Don Asker to create Monkeys in a Cage for the Australian Ballet Company.

It had over 30 performances at the Sydney Opera House.

It was a controversial ballet because it incorporated new elements into the ballet tradition.

The music was complex, but it still managed to reach a broad audience.

How do you approach composing new works compared to interpreting existing ones?

When interpreting older works, I try to imagine how they sounded when first performed — reconstructing them step by step, almost naïvely.

In composing, many modern works involve complex rhythms that require careful attention — but the spirit of discovery is the same.

What themes or ideas do you try to express in your own compositions?

I try to create vivid pictures, or to tell a story through music.

How do you see the relationship between composer and performer in today’s musical world?

I believe it’s excellent for young performers to work with living composers — even commissioning new works.

Soloists and composers can learn a great deal from each other.

Ultimately, the goal is that a composition is performed and brought to life.

International Career & Experiences

You have performed in many countries and festivals. Are there specific performances that left a lasting impression on you?

Performances in London, Chicago, Montreal, Athens, and Berlin have left wonderful memories.

Some performances I will never forget: for example, performing Busoni’s Piano Concerto during the Holland Festival at the Concertgebouw, and my performances of Sorabji’s Opus Clavicembalisticum.

The Festival of New Music in Middelburg was also an exciting occasion, working closely with Ad van’t Veer.

How does the reception of contemporary music differ across various cultures and countries?

It varies greatly.

Each country has its own unique cultural background, and audiences respond differently to contemporary music — some are more receptive than others.

This diversity is completely natural and part of the richness of performing internationally.

What have been the biggest challenges in your international career, and how did you overcome them?

Without question, preparing and performing Sorabji’s Opus Clavicembalisticum was one of the greatest challenges.

How to prepare a nearly four-hour-long work of immense complexity without collapsing on stage?

It required a careful and methodical working strategy.

Recording Busoni’s complete piano works for Philips was another major undertaking.

As a teacher, understanding and empathizing with the different viewpoints of students from diverse cultural backgrounds has been a continual, rewarding challenge.

Future & Reflection

How do you see the future of classical music and the pianist’s role within it?

Things are changing rapidly.

The potential of the internet and music streaming could become a challenge for filling concert halls — something Glenn Gould predicted many years ago.

However, the collective experience of attending a live, wonderful concert is irreplaceable and can be magnified in an extraordinary way when shared by a live audience.

What are your current projects or plans for the near future?

I am preparing several new CD recordings, looking forward to giving more masterclasses, and continuing to work with talented pianists.

Beyond music, I enjoy reading and discovering life as it unfolds.

Looking back on your career, what are you most proud of?

I am proud of the help I have been able to give composers in representing their works to interested audiences.

What message would you like to pass on to the next generation of musicians?

Remember that you are not alone — not only because of your closest colleagues but also thanks to all the wonderful people who have supported you and helped build you into who you are today.

I am always deeply grateful to them.

What do you hope your musical legacy will be?

That I have been, throughout my career, a searching musician — someone who never compromised, who always believed that we can achieve more than we think we are capable of.

Small things have often the most effect.

With a lifelong career as an international concert pianist, passionate teacher, and sought-after masterclass instructor, Geoffrey Madge now shares his personal and profound insights into piano playing.

In this new feature, he offers compact, practical suggestions — born from years of experience — for both beginning and advanced pianists.

These “Madgic Piano Insights” are not rigid rules, but playful invitations to experiment and explore. Zie Madgic tips

Afterword

PianoVrienden sincerely thanks Geoffrey Madge for his inspiring contribution. His vast knowledge, passion, and dedication to the piano are a true source of inspiration for many. His ability to connect generations through music is truly remarkable. We cherish this meeting and hope that his insights will continue to inspire many others.

Redactie e-mailadres:

info@pianovrienden.nl

Pianovrienden | 2026